"Folks, let's get something straight," Biden replied before defending the 1994 crime bill. "This idea that the crime bill generated mass incarceration—it did not generate mass incarceration."

Facts first: Following passage of the 1994 crime bill, incarceration rates in the US continued to rise for more than a decade. Experts however say it's hard to determine how much of this increase came as a result of the 1994 bill, since incarceration rates had been steadily rising since the early 1970s.

From 1973 to 2009, the incarceration rate in the US more than quadrupled, from 161 people to 767 per 100,000 nationwide, according to a study by the National Research Council. It's hard to pin that trend on one particular piece of legislation.

"No one bill created mass incarceration," Wanda Bertram, communications strategist at the Prison Policy Initiative said Tuesday, noting that the 1994 crime bill was one part of the overall "tough on crime" movement that contributed to the four decade rise in the US prison population.

One of the largest crime bills ever passed, 1994's Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act strengthened law enforcement across the country, providing federal money for new cops and prisons, as well as tightening up federal sentencing guidelines. It included a federal "three strike" provision mandating life imprisonment for certain felons convicted of violent crimes, and expanded the death penalty to include 60 additional crimes. The bill also included a ban on 18 different types of semiautomatic assault weapons for the next decade.

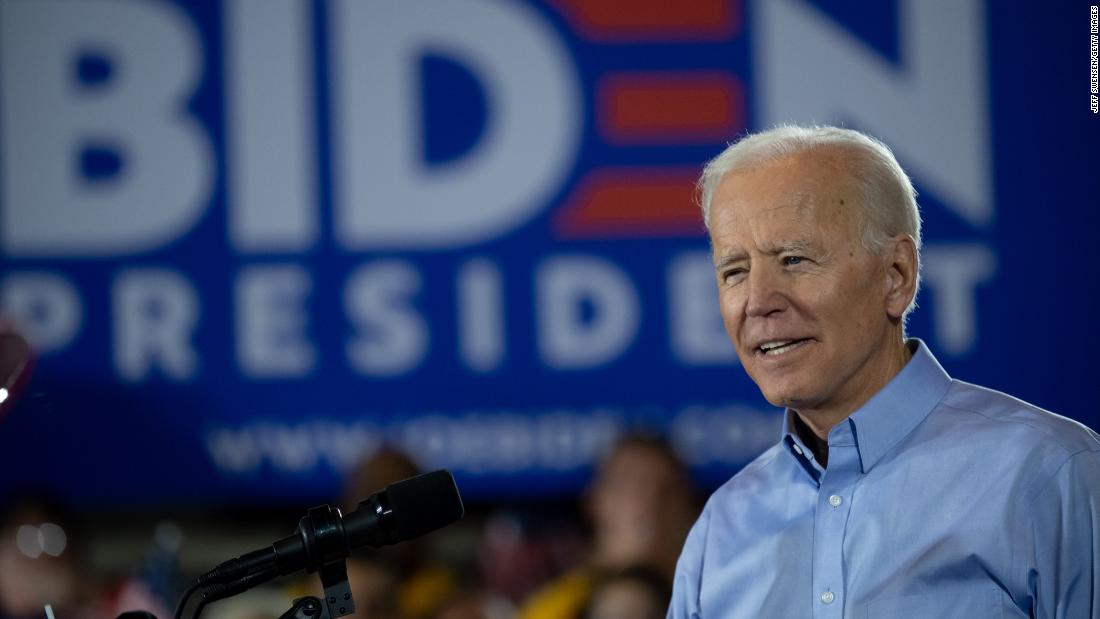

At the Nashua event on Tuesday, Biden argued that federal prisoners make up a small share of the total prison population in the US — which is true. Federal prisoners account for roughly 10% of the total number of people incarcerated in the US.

The point Biden appeared to be making was that the 1994 bill couldn't have created or greatly attributed to mass incarceration, since it only applied to violations of federal law, not state crimes.

But that misses the broader impact that federal policy can have on the way that states incarcerate, including the influence of federal money. As a report from the Brennan Center notes, the 1994 crime bill "provided funding for 100,000 new police officers and $14 billion in grants for community-oriented policing, for example."

"It is fair to say that the trajectory of increased incarceration had already begun before the 1994 crime bill," Kara Gotsch, director of strategic initiatives at the Sentencing Project, told CNN Tuesday before noting that the way Congress and the President "influence state policy is through money."

The 1994 crime bill tried to do just that in offering grants for new prisons to states who imposed truth-in-sentencing (TIS) policies, which impose mandatory minimums for time served.

Initially, the crime bill required states to pass laws mandating violent offenders serve at least 85% of their sentence before those states could receive TIS grant funds.

Even still, the influence of these federal funds shouldn't be overstated. The data is murky on how much the federal grants influenced how states make decisions on sentencing policy.

For example, a study from the Urban Institute found that out of the 16 states that changed their TIS laws following the 1994 crime bill and that qualified for federal TIS funding, "the changes were often influenced more by ongoing state reform processes rather than the federal incentive grant program."

The study says that states were already imposing their own minimum sentencing laws before the 1994 crime bill, and at most the bill "may have contributed to modest changes in sentencing structure" for a small number of states.

"The impact was as much rhetorical," said Bertram "as it was a bill that increased the number of people in prison."

No comments:

Post a Comment