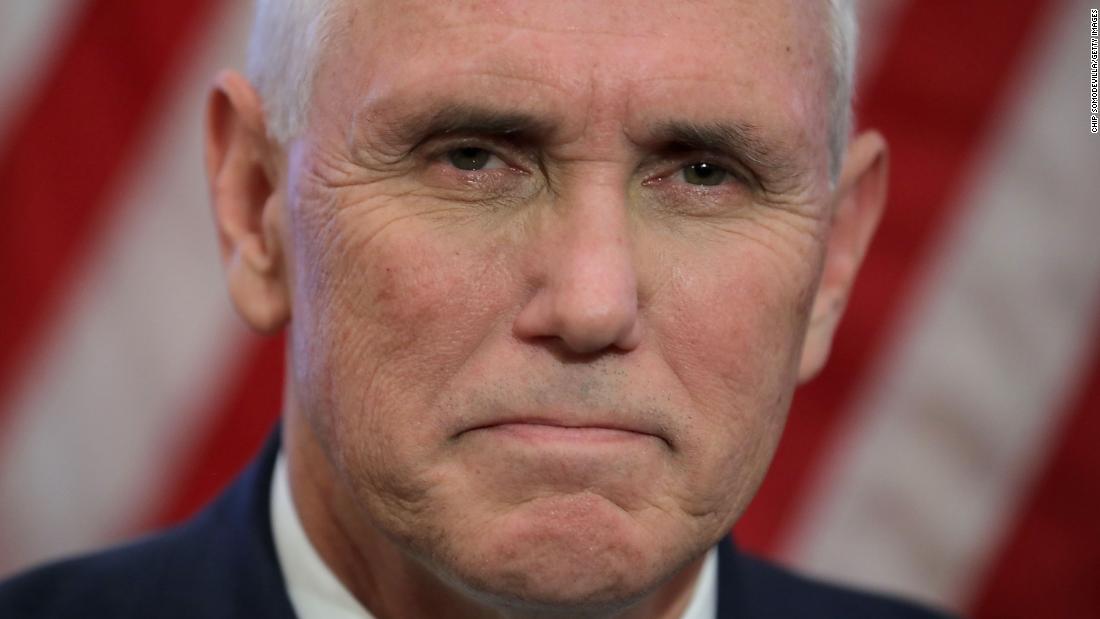

The US Labor Department announced that the economy had added 263,000 jobs in April, and that the unemployment rate had fallen to its lowest level in nearly 50 years. An hour and a half later, Vice President Mike Pence and National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow simultaneously appeared on television to deliver this message: The Federal Reserve needs to lower interest rates.

"This might be a time for us to consider about lowering interest rates," Pence told CNBC.

And Kudlow told Bloomberg: "That's our position. We think low unemployment can work in tandem with rate cuts."

Why a rate cut now would be crazy

The Trump administration has been banging this drum for months. As the stock market tanked and cracks in the economy began to appear in the final months of 2018, a rate cut didn't seem so outlandish — premature, perhaps, but not out of the realm of possibility.

But many of those cracks have since disappeared. The US economy grew at a robust annual rate of 3.2% in the first quarter, blowing past economists' expectations, even as consumer spending slowed. The unemployment rate is at 3.6%. These are not numbers that have been traditionally associated with cutting rates. They're numbers that usually suggest the Fed should hold or perhaps even raise rates.

The Fed has several tools at its disposal to speed up or slow down the economy. Its most prominent and important tool is its interest-rate-setting mechanism, which influences lending rates across the country.

When it lowers rates, lending becomes cheaper, increasing the flow of money. But inflation can become a problem.

When it raises rates, lending gets more expensive, which can slow down the economy. But it generally lowers inflation.

Why would the Fed want to slow the economy down? When it grows too fast, the economy could be in danger of overheating, which could drive inflation too high. People and companies might take on too much debt, which could make a recession more severe and come sooner than it otherwise would have. Bubbles can form in the stock market or other asset classes.

Deflation bogeyman

The Trump administration argues that inflation is not a concern. And it's largely correct: Core inflation fell to 1.4% in the first quarter, well short of the central bank's 2% target.

In an interview with CNN's Poppy Harlow, White House Chief Economist Kevin Hassett on Friday declined to say that the Fed should lower rates. But he expressed concern that inflation could fall even further — or prices could even begin to fall, a disastrous economic situation called deflation.

"There is this risk we could import deflation, and that's something that I think I know that my friends at the Fed are watching closely, that we watch closely as well," he said.

But Fed Chair Jerome Powell said it's too soon to declare victory over inflation. When asked about inflation during a press conference Wednesday, he said the dip is "transient," noting inflation ran pretty close to 2% for most of 2018.

"At the moment we don't see a strong case for moving in either direction," he said.

If the Fed were to cut rates now, it wouldn't technically be unprecedented. The Fed made precautionary rate cuts outside of recessions in 1995 and 1998. But growth was slowing then; it's accelerating now.

With a very tight labor market and growth far above its peers, most economists say the United States simply does not need stimulus. Cutting rates now would also take away weapons in the Fed's arsenal in the event of an economic downturn, when the Fed typically cuts rates. Right now, interest rates are only at 2.5%, which doesn't leave much room for rate cuts.

Even more outlandish...

That's why the Trump administration's calls for rate cuts are so outside of the norms. But the White House isn't only calling for rate cuts — they're calling for gigantic ones.

Kudlow has supported an emergency half-percentage-point cut. Stephen Moore, who President Donald Trump had eyed for a vacancy on the Fed's board, echoed the idea of a half-point cut. Moore this week removed himself from consideration but Trump said he had asked him to work with him "toward future economic growth."

Trump outdid both Kudlow and Moore this week and said he wanted a whole-point cut. The last time the Fed cut rates that much was December 2008, in midst of the the deepest financial crisis since the Great Depression. The central bank slashed rates from 1% to essentially zero at the end of 2008. It had never done anything like that before.

The administration has also suggested — but not directly called for — limiting the Fed's power.

"It might be time for us to consider that again ... the fact that the Fed looks at full employment and monetary policy and inflation," Pence told CNBC Friday. "And instead, by just looking at inflation, you would make clear there's no inflation happening here, the economy is roaring."

Pence said he has not spoken to President Trump about that idea, and Kudlow said the administration is not considering imposing any new rules on the Fed.

"It looks like us they're focused on inflation rates," Larry Kudlow told the media outside the White House. "They might decide to move to lower target rates. But we're not considering any legislation on that."

Limiting the Fed would be an extraordinary change from the norms of the past century. But not much about the Trump administration's handling of the Fed thus far can be considered "typical."

No comments:

Post a Comment